|

|

Ohio66 presents an in-depth look at the circumstances surrounding the departure of George Maharis from route 66 in the middle of the third season.

|

Author John M. Whalen's new novel, Jack Brand, is available now from these retailers: Barnes & NobleAmazon.com |

Hollywood's 8 Million Story Man

Stirling Silliphant's Scripts Journeyed Into the Heartland

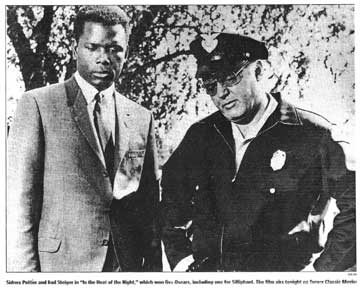

When Turner Classic Movies presents “In the Heat of the Night” tonight, it will be as part of a [two night] tribute to director Norman Jewison. The 1967 film about a black detective from Philadelphia caught in a murder case in Mississippi, and his relationship with a bigoted Southern sheriff, won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Rod Steiger's portrayal of the sheriff.

But I'll be watching the film because of its Oscar winning script by the late Stirling Silliphant.

His screenplay, based on a novel by John Ball, is taut, tense and full of irony. Police Chief Bill Gillespie is forced by the wealthy widow of the murder victim to enlist the help of homicide expert Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) in solving the case. The relationship between the two men evolves from suspicion and anger to gradual understanding. As a document of social relevance and as engrossing drama, Silliphant's script was more than deserving of its Oscar.

Yet the screenwriter evidently didn't think that highly of it. In a 1972 interview with writer William Froug, Silliphant said with characteristic frankness that he thought the film had “a curious kind of slick mediocrity” but was basically a cop-out. “I can think of 20 different television scripts that are monumental in comparison.”

He was referring to those he wrote for “Naked City” and “Route 66,” series he created in the 1950s and '60s. Anyone who remembers the work he did during television's Silver Age would have to admit he created some TV moments that have never been equaled by anyone -- including Silliphant himself.

Washington Post critic Tom Shales once wrote that “Route 66,” the classic series about two guys driving a Corvette on an existential journey across America, was “surely one of the best-written television shows of its day, maybe any day.” Of the 118 episodes broadcast during its four-year run, Silliphant wrote half. He wrote an equal number of scripts for “Naked City,” famous for its tag line “There are 8 million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them.”

Silliphant seemingly wrote nearly 8 million stories all by himself. The number of teleplays he authored is somewhere in the high hundreds. The Internet Movie Database credits him with 37 produced screenplays. “The Towering Inferno,” “Charly,” “The New Centurions,” “Telefon” and “The Slender Thread” are just a few of his titles. And the stories we've seen are only the tip of the iceberg.

Stirling Silliphant died in Bangkok in 1996 at age 78. He moved to Thailand in 1988, leaving behind once and for all “the cesspool that is Hollywood.” Before going, he donated his papers to UCLA. On the shelves of the Charles E. Young Research Library are 100 boxes full of Silliphant's scripts, treatments, proposals, personal papers enough for five writers.

I went there last summer to see for myself the literary legacy of one of Hollywood's most prolific and creative writers. The first question you ask yourself is: How could one man do all this? The second question “What drove him to do it?”

Born in Detroit in 1918, Silliphant was raised on the road until he was 5 by his salesman father and his mother, who taught him to read as they traveled. He once said that as a kid he sat in the back seat of his dad's car, watching the American landscape roll by, and dreamed up stories of heroes having fantastic adventures.

The family eventually settled in San Diego's Point Loma, later moving to Los Angeles. Silliphant went to the University of Southern California on a scholarship and graduated in three years, magna cum laude. He worked in publicity for Walt Disney Studios and 20th Century Fox, and served in the Navy during the war.

While successful as an executive, what Silliphant really wanted to do was write. “If I never tried to write, I'd have been unhappy the rest of my life,” he once said in an interview. So he quit his job and set to work. “Maracaibo,” a novel, was published in 1955 and sold the same year to the movies. Doors began to open. He was hired to write screenplays for several films, including “Five Against the House” and “Nightfall,” an adaptation of a David Goodis novel, directed by Jacques Tourneur. These years (1957-59) also found him turning out scripts for “Alcoa Theater,” “Schlitz Playhouse,” “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” “Perry Mason,” “Mr. Lucky” and other television shows.

Then came “Naked City,” followed quickly by “Route 66.” Originally called “The Searchers,” the latter was bought by CBS, but the title was changed out of concern it might be confused with the John Wayne western. Nearly 40 years after the show's debut, “Route 66” episodes are still being sold through mail-order houses, and bootleg copies are being traded by fans all over the country.

Silliphant had complete creative control over what he wrote. Themes from Pirandello, Goethe, Tennyson and other literary sources formed the basis for many of the stories. His characters didn't have "issues." Their problems stemmed from the human condition itself. Silliphant said he was trying to show the things that reveal a character's special human nature or his universal human nature."

The compelling dialogue Silliphant wrote for his “Route 66” characters was what made the show so unforgettable. He was prone to write soliloquies for these people, all of whom seemed to be searching for something. Like this stunning example from an episode set near Superstition Mountain in Arizona:

Around here everyone, even you, thinks I'm a third Apache. In Korea, I got dropped behind the lines. Believe it or not, they thought I was a third Korean. I'm a third of wherever I am, one third of whoever I'm with. Like a lizard in the sun, I blend with the landscape. It's not because I want to. All my life I've been trying to find a way of becoming three-thirds of something. Diane, you could make me three-thirds of myself.

“Route 66” was shot on location all over the United States, a feat that would be impossible on TV today if only because of the cost. Silliphant actually traveled to all the cities and towns where the stories were set, six weeks in advance of the production crew, and wrote the stories on site after spending a few days getting the feel of the place and doing research at the local library.

He had a way of coming up with offbeat titles for the various episodes. “Somehow It Gets to Be Tomorrow,” “Like This Means Father... Like This Bitter... Like This Tiger” and “How Much a Pound Is Albatross?” were typical.

“Albatross” was about a girl, played by the incredible Julie Newmar, whose family was wiped out in a shipwreck. She rides a motorcycle around the country leaving “a trail of buried albatross from coast to coast.” When a cop stops her for speeding, she tells him her only other arrest was for keeping a pet unicorn.

“Lady,” the cop says, “everyone knows unicorns are just creatures of somebody's imagination!”

“Aren't we all,” she answers.

Silliphant seemed able to bury his own albatrosses, not letting the pressures and concerns of life, career and three marriages interfere with his compulsive creative output. According to Time magazine, in 1963 his annual income topped $1 million. This was at a time when the average TV writer was pulling down $20,000 a year. He wrote 13 hours a day, seven days a week.

In the 1970s, according to his widow, Tiana Silliphant, a Vietnamese actress and filmmaker whom he married in 1974, he earned more money than any other writer in Hollywood. “Neil Simon and others got paid more,” she said, “but Stirling wrote more than anyone at the time.”

These were golden years in which he formed his own production company, did a TV series called “Longstreet” that featured Silliphant's martial-arts teacher, Bruce Lee, as a regular, and wrote “The Poseidon Adventure,” “The Towering Inferno” and two other big-box office “disaster” movies.

Still, he found it difficult to get financial backing for many of the projects he wanted to make. Locked in the UCLA vaults are dozens of screenplays that never got off the ground. They include gems such as an electrifying adaptation of Raymond Chandler's “The Long Goodbye” and scripts based on Ruth Beebe Hill's “Hanta-Yo” and Robert Lanier's “Hiero's Journey.”

There's plenty of original work as well: “The Masters,” which Silliphant intended to be, as he put it, the “American in Paris” of martial arts films, and “Between Hello and Goodbye,” which he described in a cover letter as “the most revolutionary thing written since 'Das Kapital.' ”If that were submitted to, say, Fox today, think anybody over there would even know what “Das Kapital” was?

In the 1980s he turned to writing novels, creating a series of adventures about a haunted Vietnam vet who sailed the Pacific as an antiterrorist trouble-shooter. Even during these years, though, he still turned out scripts for such films as Sylvester Stallone's “Over the Top” and the miniseries “James Michener's Space.”

In 1996 came “The Grass Harp,” based on Truman Capote's novella. Completed in Thailand only months before he died, it is Silliphant at his best. In it, two sisters play out the eternal conflict between art and commerce as the poetic Dolly (Piper Laurie) rebels against her business-minded sister Verena (Sissy Spacek), who wants to mass-produce her secret herbal remedy. The characters mirror two sides of Silliphant's own personality-artist and businessman.

Dolly says her remedy was given to her by Gypsies and shouldn't be used to make money. It was the Gypsies who taught her about the grass harp. “The wind blows through the grass,” she says, “and if you listen you can hear it tell the stories of the dead. When we die it will tell our story, too.”

Like the wind-tossed grass, Silliphant told more than his share of stories. But as I sat there in the UCLA library surrounded by the man's works, one question still remained. What drove Stirling Silliphant?

Some say our life script is written by the age of 3. If that's true, imagine a little kid in the 1920s, the Jazz Age, sitting in the back seat of his father's car, watching America race by, dreaming up stories of heroes having adventures. Maybe it's just that simple.

So, Turner Classic Movies, pays tribute to Norman Jewison, if you will. But how about, someday, a tribute to a true creative genius. One thing is sure, though. It would take more than two nights.

Washington Post - January 4, 2000

If you are a Route 66 fan, please consider joining the discussion group at:

groups.io Route 66 TV