|

|

Ohio66 presents an in-depth look at the circumstances surrounding the departure of George Maharis from route 66 in the middle of the third season.

|

Author John M. Whalen's new novel, Jack Brand, is available now from these retailers: Barnes & NobleAmazon.com |

Getting His Kicks on Route 66

Cruisin' Down the Mother Road in Stirling Silliphant's Mind

A SURFER IN MALIBU, WHO DOESN’T LET ANYONE KNOW he secretly has a job as a bus boy, tells the guy who exposes his secret, “You’re just another wave I’m going to let pass.” A girl who lost her family in a shipwreck, cruises the highways of the nation quoting Zen on a Harley, trying to out-run grief. A trail guide in Arizona who blends in everywhere like a chameleon, becoming one-third of wherever he is, says he only wants to become three-thirds of himself. These were the people you were likely to meet any given Friday night between 1960 and 1964 on the CBS television series, Route 66.

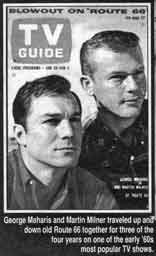

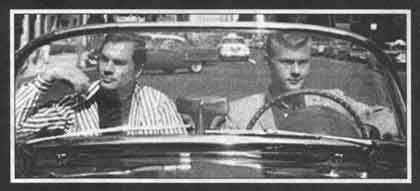

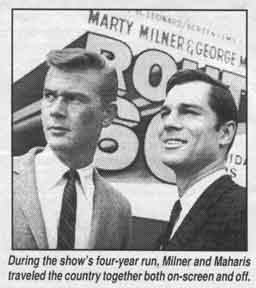

The series featured two guys, Tod Stiles (played by Martin Milner) and Buz Murdock (George Maharis), who drove the legendary highway in a Corvette searching, not so much for themselves, as for a meaning, a purpose, a place that would give them a reason to set down roots. Along the way, over four years, what they found was a 1960s American landscape populated by unforgettable characters following search patterns of their own.

Named after the great “Mother Road,” the show was filmed on location all over the United States, photographed against the backdrop of real towns and geographic landmarks.

It presented not just the actual people and places, however, but a unique vision of that time and those places—the vision of the series co-creator and chief writer, Stirling Silliphant.

Silliphant was one of the most prolific writers who ever lived. He wrote two-thirds of the 118 episodes of the series, and went on to become a big-time Hollywood writer and producer.

He won the Academy Award for In the Heat of the Night and wrote scripts including Charly, The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure, The Enforcer, and was co-producer of the Shaft series. He’s credited with 37 film titles.

No one knows how many hundreds of TV scripts he penned. He died in 1996 after expatriating to Thailand.

David Morrell, author of First Blood and Brotherhood of the Rose, says that Silliphant believed he had lived in Thailand in a past life. He told Morrell, a close personal friend, that he was “going home.” He held a yard sale at his Beverly Hills home, sold everything, and moved to Bangkok in 1989. He never came back.

But in 1960, when Route 66 premiered, Silliphant was 41, strong, energetic, and full of stories to tell. In fact, only the year before, he had written 38 of the 39 episodes of Naked City starring James Franciscus. Like that series, Silliphant himself, still had about 8,000,000 stories left to write.

He traveled to all of the locations used on Route 66, arriving six weeks ahead of the production crew. He said in newspaper interviews at the time, that he would walk around, get a feel for the place, go to his motel room, and, in a few days, come up with an original script using the setting and characters that seemed relevant to their backgrounds.

In an Oregon fishing town, he wrote about an angry dock fighter, with a buried past, who drank and brawled to forget the men in his Army squad that he led into ambush. In Phoenix, he wrote about a crop duster, a former English airman who believed he carried a jinx that brought death to anyone he let get close. In New Mexico, he wrote about a nuclear scientist who lead a group of followers down inside the Carlsbad Caverns because he believed that a nuclear attack was about to end the world.

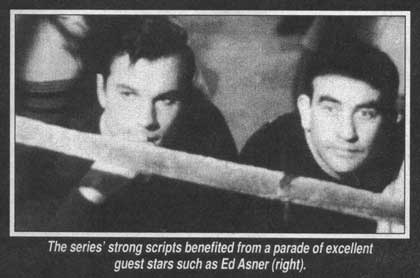

Every week a different place, every week a new and compelling story. Critics talk about the Golden Age of TV in the 1950s but, in many ways, the Route 66 years stand alone in terms of quality writing and acting. The show attracted some of the top names in film, stage, and TV as guest stars. People like Joan Crawford, Michael Rennie, Dan Duryea, Lew Ayres, and many others asked Silliphant to write scripts for them. In addition to the top names, many unknowns like Robert Redford, Harrison Ford, and Ed Asner got their start on Route 66. Directors like Sam Peckinpah, Elliot Silverstein, and Robert Altman also worked on the series.

But it was the stories that got you hooked, that brought you back every Friday night at 8:30. Stirling Silliphant’s stories captured America in the 1960s. They were stories about a post-war American society that had a sub-population made up of the dispossessed, the disenchanted, society’s rejects. The guys in the Corvette had rejected conformist America in favor of a life on the road, so they could afford to be a little more generous to the disenfranchised.

Silliphant’s scripts often focused on characters that mainstream society found unacceptable. The stories always scratched through surface appearances and, through the course of events, we usually found our first impressions about these “lost souls” were wrong. And in almost every program the services and institutions society sets up to help these people were shown to be inadequate. It was usually up to Tod and Buz to help these characters find their salvation.

In “Birdcage on My Foot,” Robert Duvall played a heroin junky in Boston who tries to steal the Corvette. The local public health service isn’t equipped to deal with his problem, so Buz helps him go cold turkey.

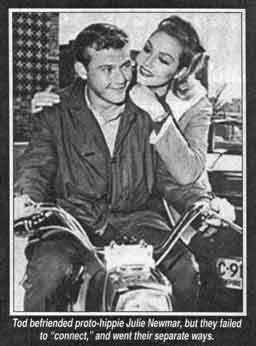

In Tucson, they meet up with Vicki Russell, the Zen-drenched babe escaping grief on a Harley. Played by Julie Newmar, Vicki ends up in jail when she amuses a bored cop by deliberately running a red light and leading him on a wild chase through the city. Only Tod and Buz will go her bail, and when she appears in court, the judge decides the best way to handle her is to banish her from the city limits. Tod and Buz try to connect with her but she’s somewhere on another cosmic level, and, in the end, they part on the highway, the motorcycle going south, the Corvette headed north.

In El Paso, a woman returns to her job at a cotton oil company alter spending seven months in prison for a crime she didn’t commit. Even a well-meaning parole officer believes she really did it. But Tod and Buz prove she was framed by wealthy cattleman, Lee Marvin, who wanted to punish her for resisting his advances.

A town in Mississippi has isolated itself from the world because of a dark secret going back to World War II. Tod and Buz arrive and are nearly lynched for discovering the secret, but by revealing the evil, the two drifters not only escape the noose but also heal the town.

Sometimes the two central characters were the focus of the story. Tod had been raised in wealth and received a Yale education, but when his father died, he found out the business he owned was bankrupt. The only souvenir of his former life is the Corvette his dad had given him just before he died.

Martin Milner, who began acting in movies in 1946, was perfect for the part of the erudite, yet down-to-earth Yale graduate, whom circumstance had sent out on a highway odyssey. Tod was the intellectual, who was able to quote Shakespeare and Freud, and was something of an idealist. He often had his ideals challenged by some of Silliphant’s storylines.

In “...He Shall Forfeit His Dog and Ten Shillings to the King,” he witnesses the mean, murderous behavior of a posse searching for two suspected killers in the desert near Superstition Mountain, Arizona. Their actions seemed based on the idea that you can’t feel important unless you hurt somebody else. At the conclusion of the story, he’s left standing in the desert shouting, “I don’t believe that I’ll never believe that!”

Tod always seemed to fall in love with the wrong girl. In “Suppose I Said I was the Queen of Spain,” he falls for Lois Nettleton, who turns out to be some kind of kook who can’t remain in one identity for very long.

In “The Cruelest Sea of All,” he actually gets involved with a mermaid, played by Diane Baker. In Weeki Wachee Springs, Florida, he’s working at a tourist attraction featuring live “mermaids” performing an underwater show. One of the girls turns out to be an actual real-life mermaid who swam in from the Sargasso Sea. He falls for her, but thinks the mermaid act is just some kind of “shtick” to get publicity.

He’s too “smart” to think she could be for real. In the end, he pays for his inability to believe with a broken heart, when she leaves him to return to the sea.

Buz didn’t fare much better with the ladies. In “A Month of Sundays,” set in Butte, Montana, he falls for Anne Francis—a Broadway actress who has come home to die. Here again, the medical community can do nothing for her, and even a clergyman seems to provide no solace for the dying woman. It’s only Buz, who says, “Her favorite day is Sunday. I’ll give her a month of Sundays,” who is able to ease her pain.

Buz was an orphan, raised on the streets in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of New York. Less educated than Tod, he acted more from instinct. When he witnessed a wrong being committed, he didn’t stop to think about it. He just swung into action.

The part fit George Maharis like a glove. A New York method actor, he was dark, brooding, and always on the verge of exploding.

In “The Newborn,” when the Santa Fe ranch owner he worked for told him to get a rope to tie up a pregnant Indian woman, Buz jumped off a wagon and said, “Mr. Ivy, I quit,” and socked him on the jaw.

In the third year of the show, Maharis dropped out because of illness. Glenn Corbett joined the cast in 1963, playing Lincoln Case, a special forces Army Ranger, just home from Vietnam. Even at this early stage of U.S. involvement in that conflict, Silliphant wrote about its impact on our society.

Another displaced person, unable to readjust to his former life in a small Texas town, Linc joins up with Tod on the road, leaving the past behind. In one particular episode, his experience as a jungle fighter comes in handy when he goes into the Florida Everglades with Tod and Sessue Hayakawa in search of a former World War II flying ace, played by Jack Warden. Warden is sick of the banality of his current life and has crashed his plane in the swamp deliberately. Hayakawa is an old enemy, a former pilot for the Land of the Rising Sun, who now lives an unrewarding life with his son and daughter-in-law in Baltimore.

Tod, Linc, and Hayakawa parachute over the spot where the wreckage was sighted, and search until they find “Sans Everything” written in the mud. It’s from the “Seven Ages of Man” speech in Shakespeare’s As You Like lt. “Sans eyes, sans teeth, sans everything.”

They find him in pretty bad shape, and he doesn’t want to go back. He wants to be left there to die. They bundle him up anyway, make a raft, and float him up river, back toward civilization. On the way, Hayakawa reminds Warden of their glory days and the dogfight in which they each thought the other had been killed.

There’s a shot of a Zero and a Navy Hellcat, flying over their heads there in the Everglades, as they recall the old days. Then Warden, suddenly inspired to live again, looks at his former foe, and says, “Alright, let’s get this tub moving,” and dies.

“What a senseless way to die,” Linc says.

Hayakawa answers, “He died well. He died wanting to live. One smiles.”

Route 66 was television as it had never been before, and has never been since. It presented a rare and unprecedented view of America in the ’60s — the good, the bad, and the ugly. It was individualistic, unconventional, and totally on the side of society’s underdogs.

And every week, somehow, Silliphant always managed to grab you, shake you up, make you aware that you’re alive. Like that World War II ace played by Jack Warden, Silliphant made you want to say, “Alright, let’s get this tub moving,” The highway the show was named for exists now only in crumpled fragments, in some areas of the midwest and the west—long ago made obsolete by the Interstate Highway system. But the towns, the characters, the stories—the vision of Stirling Silliphant—will live on for as long as there are fans left to remember.

If you are a Route 66 fan, please consider joining the discussion group at:

groups.io Route 66 TV